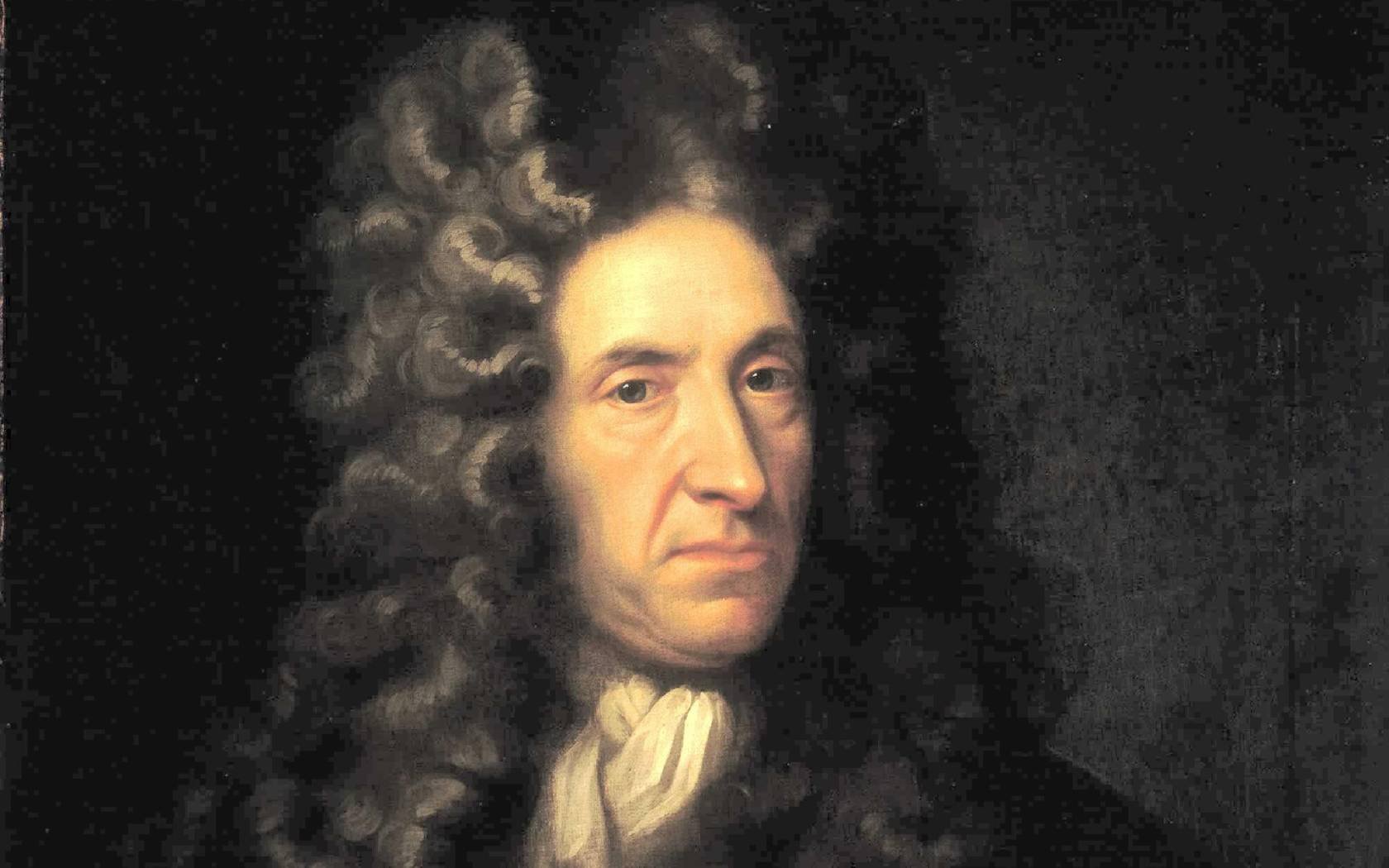

Daniel Defoe’s journeys of the mind

- December 30, 2024

- Malcolm Forbes

- Themes: Books, Culture

Three centuries on from the publication of Daniel Defoe’s A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain, the English writer's travelogue remains unsurpassed.

In his novels, Daniel Defoe’s eponymous protagonists travel far and wide and then yearn for a return to English shores. Robinson Crusoe hopes to be rescued from his ‘Island of Despair’. Moll Flanders craves a change of scene when married life in Virginia doesn’t work out: ‘I hankered after coming to England, and nothing would satisfy me without it.’ And, after passing from one protector to another in continental Europe, Roxana sails past the country she was ‘bred up in’ and is filled with a desire to break free and settle there: ‘I secretly wish’d, that a Storm wou’d rise, that might drive the Ship over to the Coast of England, whether they wou’d or not, that I might be set on Shore any-where upon English Ground.’

In his varied nonfiction, Defoe engaged with many different aspects of English life and history. In ‘An Essay Upon Projects’ (1697) he put forward suggestions for the economic and social improvement of England. Among his many political and religious pamphlets was the satirical (and, it was decreed, seditious) tract The Shortest Way with the Dissenters (1702), which proposed extreme measures to deal with the rebels that threatened the sanctity of the Church of England. His 1704 book The Storm described how ‘Horror and Confusion seiz’d upon all’ when a hurricane from the north Atlantic battered Britain one year earlier, while one of his masterpieces, A Journal of the Plague Year (1722), consisted of ‘Observations or Memorials, of the most Remarkable Occurrences, as well Public as Private, which happened in London during the last great Visitation in 1665’.

Defoe also grappled with the notion of Englishness in his bestselling poem The True-Born Englishman (1701). In his preface he urged his fellow countrymen to be more tolerant towards foreigners. ‘Methinks an Englishman, who is so proud of being called a goodfellow, should be civil,’ he wrote; ‘and it cannot be denied but we are in many cases, and particularly to strangers, the churlishest people alive.’ In a succession of savage heroic couplets, Defoe, a staunch supporter of William III, railed against xenophobic opponents of the Dutch-born king. At the same time, he scoffed at the myth of a pure ‘English’ race – one that was composed of Romans, Gauls, Saxons, Danes, Normans, Picts and Scots. ‘Fate jumbled them together, God knows how / Whate’re they were, they’re True-Born English now.’

Defoe didn’t just explore facets of England and Englishness, he also explored the country physically, on a series of journeys. On each of his ‘circuits’ he traversed main thoroughfares, navigated roads less travelled and visited all kinds of towns in England, Wales and Scotland, all the time recording their trade, traditions and topography – ‘whatever is curious and worth observation’. This year marks the 300th anniversary of the publication of the first volume of A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain. Two more volumes followed in 1725 and 1726; each one proved to be financially rewarding for its author. Today the book isn’t as well-read as it should be, but it remains a triumph of travel writing.

One of the Tour’s strengths is the way Defoe candidly and succinctly (in his words, ‘no blusters, no rhodomontadoes’) described cities and towns. Harwich, he writes, is ‘a town of hurry and business, not much of gaiety and pleasure’. Lincoln is ‘an ancient, ragged, decayed, and still decaying city’. Maidstone is a pleasant place where ‘a man of letters, and of manners, will always find suitable society, both to divert and improve himself’. Plymouth is ‘a town of consideration’. Gloucester a ‘middling city, tolerably built, but not fine’. Poor old Darlington ‘has nothing remarkable but dirt, and a high stone bridge over little or no water’.

Some descriptions allow us to trace great changes over the centuries. There are cities that have become shadows of their former selves. ‘I believe there is more business done in Hull than in any town of its bigness in Europe,’ Defoe declares. Then there are cities like Bath – today quiet and genteel but for Defoe a bustling, vibrant pleasure resort, ‘taken up in raffling, gaming, visiting, and in a word, all sorts of gallantry and levity’. (Moll Flanders echoes this, but is also more scathing when she calls it ‘a place of gallantry enough; expensive, and full of snares’.)

In other descriptions, Defoe reveals how much places have improved in the years before his arrival. War ruined towns, but plague ravaged populations, and in the plague year of 1665, Colchester was ‘severely visited’, claiming 5,259 lives. Shrewsbury – for Defoe one of the most flourishing towns in England – is ‘a town of mirth’ and good health, but a ‘blot’ still stains its reputation, for it was here in 1551 that ‘that unaccountable plague, called the sweating sickness’, broke out, before spreading through England and abroad.

Again and again in the Tour, Defoe reached out and drew comparisons with places on the Continent or further afield. In doing so, he showed how well-travelled he was. Yarmouth ‘makes the finest quay in England, if not in Europe, not inferior to that of Marseilles itself’. Cambridge’s Stourbridge Fair, once the largest in Europe, is superior to ‘the fair at Leipsick in Saxony, the mart at Frankfort on the Main, or the fairs at Neuremberg, or Augsburg’. Not only is it ‘the greatest in the whole nation, but in the world’. The North Terrace of Windsor Castle, where Elizabeth I liked to walk, is unlike anything he has seen – ‘neither at Versailles, or at any of the royal palaces in France, or at Rome, or Naples’. The mountains of South Wales put him in mind of the Alps, and the fables he hears from Welsh country folk about their lakes are similar to those he has been told by ‘Switzers’. The ‘vastly strong’ one-arch bridge spanning the River Ouse in York – ‘without exception, the greatest in England’ – is, according to some people, ‘as large as the Rialto at Venice, though I think not’.

Perhaps unsurprisingly for a London-born man, Defoe provided special coverage of the capital. Previously, London had loomed large in some of his fiction. In his study of the English novel, Defoe to the Victorians, David Skilton argued that ‘In Moll Flanders, Colonel Jack and Roxana, Defoe presents London so authentically that his novels constitute social records as well as fictions’. In the Tour, Defoe actually gave us that social record of the city. He takes us on scenic excursions through London: down streets, across squares and along the river, pointing out and discoursing on a variety of sights – ‘all the buildings, places, hamlets, and villages contained in the line of circumvallation’. His chatty, lively commentary incorporates palaces, hospitals, schools, libraries, prisons, and churches that are ‘rather convenient than fine, not adorned with pomp and pageantry as in Popish countries’; workhouses, customs houses, coffee-houses, meeting houses, pest houses and houses of correction; buildings for trade and commerce, government and administration, law, royalty and entertainment; plus monuments, quays, dockyards, city gates and markets for fish, flesh, fruit, herbs, hay, leather, coal, corn and cattle.

At one juncture, Defoe abandons all objectivity and gets carried away with what he sees before him: ‘a fair prospect of the whole city of London it self; the most glorious sight without exception, that the whole world at present can show, or perhaps ever could show since the sacking of Rome in the European, and the burning the temple of Jerusalem in the Asian part of the world’.

If the Tour is pleasingly stuffed with Defoe’s impressions of places, glowing or otherwise, it is thin on certain hard facts. Defoe explained he would not touch on geographical matters such as ‘the longitude of places’ and ‘the buttings and boundings’ of counties. He would also serve up little on sites or landmarks of historical interest. He was a traveller, not a tour guide; ‘antiquity’, he says, ‘is not my work.’ In his preface to the first volume, Defoe offers a disclaimer to his reader. ‘If antiquity takes with you, though the looking back into remote things is studiously avoided, yet it is not wholly omitted, nor any useful observations neglected.’

For the most part, Defoe was as good as his word, and merely commented on historical features rather than lectured on them. But when either a building or the scene of a battle lost and won merited it, he changed tack and imparted fact-filled trivia, often by drawing on William Camden’s 1586 topographical and historical survey Britannia. In Canterbury, Defoe recounts the illustrious dead buried in the vaults of its cathedral, from Thomas Becket to Henry IV to Edward the Black Prince; in Bury St Edmunds, he tells of the death of a martyr-king, the destruction of a monastery and the remorse of a Danish marauder.

Defoe spiced some of his summaries with stories of crime and punishment. In one, we learn that Lord Sturton was hanged in Salisbury in 1557 for committing ‘a very unhappy murther’. Sturton was denied a beheading, ‘the usual grace of the Crown’. Instead, Queen Mary decreed that he die at the gallows ‘like a common malefactor’. A bishop told his friends that the body could be buried in the cathedral on the sole condition that Sturton’s silken noose was pinned above his grave as a reminder of his crime. They agreed and Defoe observed and approved this ‘mark of infamy’. Elsewhere, another story of an execution, one told to Defoe by ‘the Hallifax people’, is blackly comic. As the axe fell on the neck of the criminal, ‘it chopped through with such force’ that the head flew out and landed in the hamper of an unsuspecting woman on her way to market.

That story may be a folk tale or a tall tale – or as Defoe puts it, ‘’tis reasonable to think the whole tale is a little Yorkshire’ – but it is an example of one of the many diverse components that keeps the Tour consistently engaging. Defoe also ensures readers stay onboard by occasionally switching his focus and prioritising people over place. Not everyone appears in a good light. Cornish ‘country people’ are savages. Cornish hurling, he says, is ‘a rude violent play among the boors, or country people; brutish and furious, and a sort of an evidence, that they were, once, a kind of barbarians’. When storm-tossed merchant ships hit rocks or run aground, ‘voracious country people scuffle and fight about the right to what they find, and that in a desperate manner, so that this part of Cornwall may truly be said to be inhabited by a fierce and ravenous people’. Shipwrecked seamen come ashore ‘where they find the rocks themselves not more merciless than the people who range about them for their prey’.

Defoe found more civilised people in Lyme Regis: ‘a general freedom of conversation, agreeable, mannerly, kind, and good runs through the whole body of the gentry of both sexes, mixed with the best of behaviour, and yet governed by prudence and modesty’. But in some places, a person with the best of behaviour could make a wrong move and find their reputation irreparably tarnished. Tunbridge Wells is so full of ‘fops, fools, beaux and the like’ and so awash with ‘tattle and slander’ that even a woman of honour and virtue may come undone. Defoe gravely adds: ‘some say no lady ever recovered her character at Tunbridge, if she first wounded it there’.

The Tour has its flaws. Great swathes of it appear to have been written hastily. Defoe gets names wrong and arbitrarily flits between two variations (Liverpoole, Leverpool). His estimates of populations are frequently way off the mark. Key places are underrepresented. There are careless mistakes: ‘Chester has four things very remarkable in it,’ he writes, before listing five examples. He digresses, repeats formulations (many a town is large, populous and well-built) and resorts to sweeping statements: ‘I believe this may be said with truth, that in no city in the world so many people live in so little room as at Edinburgh.’ As demonstrated above, Defoe is also overly-fond of strengthening a pronouncement with a superlative. If the purpose of his tour had been to pinpoint Britain’s perfect patch then he would have drastically cut short his travels, for at an early stage in his first circuit he tells us: ‘I had the advantage of making my first step into the county of Kent, at a place which is the most delightful spot of ground in Great-Britain.’ It is there, in Greenwich, that Defoe enjoyed ‘the most beautiful river in Europe; the best air, best prospect, and the best conversation in England’.

At times, Defoe recycled his singular praise for a place. ‘In a word, there is no town in England, London excepted, that can equal Liverpoole for the fineness of the streets, and beauty of the buildings,’ he proclaims. But while travelling north of the border, Defoe found another city’s streets just as impressive. Glasgow’s four main streets are ‘the fairest for breadth, and the finest built that I have ever seen in one city together’, he claims; ‘in a word, ’tis the cleanest and beautifullest, and best built city in Britain, London excepted.’ Then there is Cambridge, apparently the ultimate place of study: ‘to any man who is a lover of learning, or of learned men, here is the most agreeable under heaven’. But later, Defoe either forgot the status he afforded Cambridge or he deliberately revised it. Oxford turns out to be ‘a noble flourishing city, so possessed of all that can contribute to make the residence of the scholars easy and comfortable, that no spot of ground in England goes beyond it’.

Perhaps the biggest criticism that can be levied against the Tour relates to the way Defoe acquired and collated his source material. He travelled extensively to research his book, mainly in 1722. However, he also drew on a number of journeys he had made earlier. One of his biographers asserts that Defoe derived most of his content from his nationwide travels as a merchant between 1685 and 1690. It is just as probable he made use of his experience crisscrossing the country as a spy for the Tory statesman Robert Harley – particularly on intelligence-gathering missions in the run-up to the 1707 Act of Union. How up-to-date was Defoe’s information and how reliable were his memories of his travels? We know he consulted previously published texts. So why does he tell us that ‘the accounts here given are not the produce of a cursory view, or raised upon the borrowed lights of other observers?’

Defoe was a talented journalist, which leads us to hope that he set out to collect the full facts and report the whole truth in his book, or at the very least present as accurate a picture as possible. But he possessed a riotous inventive streak and had form as a fabricator. A Journal of the Plague Year might purport to be an eyewitness account of that ‘great Visitation’, but in actual fact Defoe was only five years old in 1665. The book can be read as fiction or nonfiction. (Indeed, the scholar Michael Schmidt says it is ‘not historical fiction so much as historical imagination’.) Defoe was also that new breed of writer, a novelist, who delighted in making things up. How much creative licence did he take with his Tour? Can we class it as entirely factual, or is it safer to categorise parts of it as factualised fiction?

Yet these queries and quibbles don’t detract from the book’s brilliance. It is a deft blend of guide book, travelogue and gazetteer. It weaves together reportage, personal commentary (and perhaps recollection), travel yarns, anecdotes, legends and vital statistics. It gives valuable insight into Britain’s past endeavours, her contemporary society and her economic prospects. Edifying and entertaining in equal measure, and the most authoritative such survey of its day, the book mapped the lay of the land and analysed the state of the nation, informing readers about the country they lived in – one that with the forging of the Union just 17 years earlier, had changed shape and identity.

We can argue that the Tour was also hugely influential. It paved the way for other peripatetic writers whose works helped establish travel writing as the dominant literary genre of the second half of the 18th century. Among the most notable publications were Tobias Smollett’s raucous epistolary novel The Expedition of Humphrey Clinker (1771), which comically charted the progress of a family party through Britain (‘this country would be a perfect paradise’, a character says of Scotland, ‘if it was not, like Wales, cursed with a weeping climate’) and his caustic record of a disastrous European trip, Travels Through France and Italy (1766). Two years later, Laurence Sterne’s take on European travel, A Sentimental Education, combined gentle humour with moral enquiry. Samuel Johnson’s Journey to the Western Isles of Scotland (1775) and James Boswell’s Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides (1785) centred on the geography and ethnography from their shared ‘jaunt’, and at the same time highlighted the pleasure of exploring a country with a trusty travelling companion.

Defoe’s book was more colourful and more comprehensive than any of the above. It also stands apart from two substantial travel books which appeared the following century. Posthumously published in 1888, Celia Fiennes’ travel memoir Through England on a Side-Saddle described a series of journeys the writer made at the end of the 17th century to improve her health ‘by variety and change of aire and exercise’. William Cobbett’s Rural Rides (1830) was an account of his travels on horseback through the English countryside.

While these books are informative and evocative, they lack the scope, the subtlety, the dynamism, the perceptiveness and the multifariousness of Defoe’s Tour. Fiennes offers a quaint portrait of pretty landscapes and encounters with relatives and acquaintances. Cobbett, a self-proclaimed ‘South-of-England’ man, who vented his ire against expanding cities, gives us a limited picture that cuts out the north and eschews urban life. He also evinces a limited outlook, coming across as quick-tempered and given to opinionated, italicised generalisations. ‘All Middlesex is ugly,’ he rants. It is interesting to compare one of his verdicts with one of Defoe’s. In the Tour, Defoe provides this brisk yet animated and illuminating sketch of a Surrey town:

From Stanes therefore I turned S. and S.E. to Chertsey, another market-town, and where there is a bridge over the Thames. This town was made famous, by being the burial place of Henry VI till his bones were after removed to Windsor by Henry VII, also by being the retreat of the incomparable [Abraham] Cowley, where he lived withdrawn from the hurries of the Court and town, and where he died so much a recluse. From this town wholly employed, either in malting, or in barges to carry it down the river to London; I went away south.

In contrast, Cobbett only recounts a visit to Chertsey’s livestock fair. ‘I did not see any sheep,’ he grumbles. ‘Every thing was exceedingly dull.’

Three centuries on and nothing has rivalled Defoe’s book. This is unfortunate. The country he travelled around went on to be marked and moulded by industrial revolution, social reform, the rise and fall of empire and world wars. A new tour by a new writer is long overdue. But it is doubtful than anyone anytime soon will follow in Defoe’s footsteps around Britain or produce a work that, as he put it, gives ‘a view of the whole in its present state’.